Why cultivating emotional intelligence among toddlers has become more urgent

In previous years, responses to student emotions and conflicts would vary by teacher, often based on training or experiences, said Lauren Cook, chief executive officer at Ellis, which has three locations in the city. In late 2022, Ellis adopted a formal social and emotional learning program — SEL for short — for the first time, pairing online training for teachers and classroom-based resources with visits from social-emotional coaches.

The school is part of a small but growing wave of early learning programs seeking to build or expand their social-emotional component in the wake of a pandemic that has led to more challenging student behavior and unprecedented turnover among child care workers. In Connecticut and New York, for example, home-based child care providers have sought out more formal training in SEL. More than 250 preschool classrooms in Florida and 150 Head Start classrooms in the northeast have adopted a new SEL curriculum aimed specifically at addressing the pandemic’s toll on young children. And the federal government recently put millions toward expanding SEL programs in the earliest years.

The need is real. Research and educator surveys show that young children have been severely impacted by pandemic-related stress and trauma, such as the death of loved ones and food and housing security, as well as limited opportunities for social interaction outside of the home. Parents and educators report more young children are hyperactive, fearful, aggressive, and have trouble interacting with peers. Their teachers, too, can benefit tremendously from increased support in coping with sometimes difficult classrooms and behavior.

“Coming out of the pandemic where we’ve seen so much more challenging behavior and just really difficult experiences that the kids have gone through that are showing up in their behavior,” said Cook. “It’s even more important to be devoting time and resources to this.”

Yet even programs for the youngest kids have not escaped some of the broader pushback and controversy over SEL, which opponents have accused of promoting critical race theory, the idea that the framework for racism is embedded in society, among other things. Last year in Louisiana, for instance, lawmakers and parents claimed that the state’s new early learning standards might include “potentially divisive concepts,” such as gender identity and systemic racism, within SEL lessons. (Those standards were approved twice by the state’s top school board, but early this year the school board re-opened public comment.)

“We get to states where, suddenly, SEL has become a taboo word to use,” said Mary Louise Hemmeter, a professor of special education at Vanderbilt University. In January, Hemmeter was awarded a nearly $12 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education for the nationwide expansion of a social-emotional learning model that she developed for child care programs, pre-K, and kindergarten classrooms. In some communities, Hemmeter said, she’s very cautious in the language she uses to describe the SEL programming.

The occasional pushback has not significantly slowed SEL’s spread for the youngest students, however. Early childhood experts say the goal is quite simple: teaching children basic social, emotional and cognitive skills and how to build empathetic relationships with others.

“If you ask kindergarten teachers what they want children to be able to do when they come to kindergarten, it’s not write their name or know their letters,” Hemmeter said. Kindergarten teachers “want [kids] to be able to follow directions. They want them to be able to persist at difficult tasks. They want them to be able to get along with other kids and work together and be able to engage in classroom routines.”

When Cook and her colleagues at Ellis Early Learning started looking into SEL in 2020, they were motivated in part by wanting to ease the transition to elementary school, especially for students who have experienced trauma. More than two-thirds of the program’s families face economic hardship and receive financial assistance from the state to pay tuition. More than 25 percent of children have active cases with the city’s foster care system.

“There are big feelings, there have been traumatic events that kids have witnessed,” said Cook. “We’re giving [kids] autonomy and saying, ‘All of your feelings are valid. You get to feel them in a way that is safe for you and others.’”

“We really need to build capacity in these areas earlier so by the time our kids get to K-12, teachers there will have a much easier time, and the child will have a much easier time,” she added.

In any given classroom at Ellis, a visitor will now hear the same refrains echoed throughout the day:

“Use your words!”

“How do you think your friend is feeling?”

“How did that make you feel?”

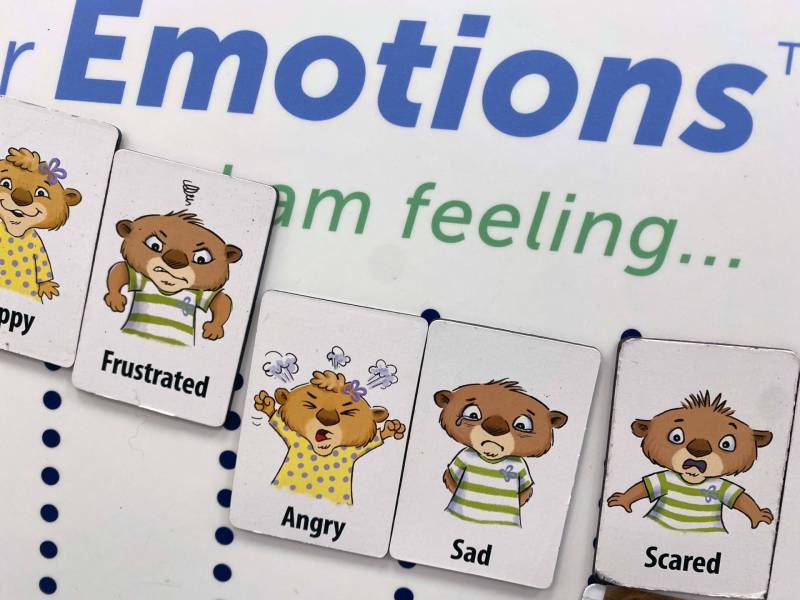

Each day, teachers ask students to take time to identify their feelings by affixing their picture next to the name of the emotion they’re feeling on a chart. On a recent February morning in a preschool classroom, for example, most of the class chose happy or excited, but one student selected “frustrated.”

This illustration of feelings helps teachers know how to support individual students. They might give a frustrated or angry child a break in a calming corner, for instance. Or they might know to offer up a hug, a song, a chance to play with items from a sensory box or help practicing deep breathing.

The focus on building emotional intelligence starts even before students can walk or talk. In a bright infant classroom, lead infant teacher Jamalia Sheets held up a card with a picture of a cartoon animal showing a sad face. “Look, she’s sad! Can we make a sad face?” Sheets and her two co-teachers all mimicked a sad face and made crying sounds. “Let’s make an angry face,” she said, flipping to another card and modeling an angry face. A 14-month-old toddling around the circle of teachers mimicked the angry face. “Oooh look at that angry face! That’s what I’m talking about,” Sheets said, before moving on to model excitement, worry and surprise.

Teaching emotional competence from birth is a key tenet of “begin to ECSEL,” the program Ellis has adopted. Created by the Boston-based Housman Institute,* the approach capitalizes on the rapid brain development that happens in the first few years of life, said Donna Housman, founder of the institute. “When the brain is overwhelmed by negative emotions, it can’t learn,” she said. “Having the skills to deal with and regulate our own emotions calms the brain.”

Ideally, these skills should not be imparted randomly, experts say. “Where it’s done really well, you can see [SEL] woven into everyday practices in the classroom,” said Tia Kim, a developmental psychologist and the vice president of education, research and impact for the Committee for Children, which developed a global SEL program called Second Step.

A growing body of research shows the long-term benefits of quality social-emotional learning for children: an increase in academic performance, better classroom behavior and higher levels of well-being as young adults. One study found that low-income children with stronger social problem-solving skills at the start of preschool learned math skills faster.

Moreover, research shows that providing strong social-emotional training to teachers in early learning programs can help lessen chronic and frequent preschool suspensions — if those supports are done right.

“When SEL contributes to reducing teacher stress, that could benefit expulsion rates,” said Kate Zinsser, an applied developmental psychologist and associate professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago and the author of “No Longer Welcome: The Epidemic of Expulsion from Early Childhood Education.” But, she added, “poorly implemented SEL supports could increase teacher stress.” That poor implementation includes simply handing a teacher “yet another curriculum” without enough training or observations to enable the teacher to roll out SEL effectively.

It can be hard for educators to decipher which SEL programs are beneficial and which are not. At Ellis, officials said they were drawn to the Housman Institute’s program due to a clear record of successful outcomes for children, but investigating alternatives can take time.

Cook is already seeing positive signs that the program is having an impact. Students are better able to work through upsetting situations at school. And parents have reported that their children are showing more empathy and curiosity about emotions and can more clearly identify their feelings.

But one of the most striking impacts has been on Ellis’ teachers, who now have more strategies to handle a stressful job, the many challenges that come with educating young children, and their own stressors outside of work.

While other industries have rebounded since the pandemic hit, the early childhood industry is still lagging, struggling to find staff and keep classrooms and programs open. Larger policy and economic changes are needed, such as more federal funding and higher pay for teachers, yet some educators say SEL can boost teacher mental health and retention, a goal Cook has at Ellis.

“We need this job to be easier for people, because it’s hard,” said Cook. “It can only be easier when we equip them with the right tools so they can manage their class successfully.” She hopes that with the new emphasis on SEL, “teachers will feel they have a much stronger capacity to manage their classrooms in a healthy, positive way, and also that the children have even better days.”

For Sheets, the infant room teacher, the embrace of SEL has helped her better regulate her emotions as well as those of her students — making it easier to balance a stressful, physically taxing job and motherhood. The curriculum used by Ellis includes several online teacher training modules on topics like identifying and managing emotions and how to deal with stress. The goal is to help teachers manage their own emotions and mental health first so they can then better help children. “Understanding emotions within yourself, understanding emotions within children helps you go a long way to helping them foster healthy child development,” Sheets said.

It was during one of these online training sessions that Sheets first heard the term “toxic stress,” or long-lasting stress due to frequent or prolonged adversity. Sheets realized then that experiences from what she said was a rough childhood, including five years living apart from her mother, were still impacting some of her emotional responses as an adult. The training has helped her manage her own stress, which translates into how she responds to children and models behavior. “Being able to pick up on certain things that could be stressors and regulate them before you come into the professional environment with them, it’s been very helpful,” she said.

Nationwide, not all child care programs have the staffing and funding that make it possible to access — and pay for — the quality SEL training and support that experts say is most likely to make a difference for teachers and children alike. In Bridgeport, Connecticut, the nonprofit All Our Kin is trying to fill that gap, offering social-emotional training to more than 550 home-based educators in Connecticut and Bronx, New York.

Julia Zamora, a Connecticut-based home child care provider, had never had SEL training until she started working with a coach from All Our Kin. Zamora, who spent 22 years in her home country of Ecuador teaching older students, primarily teenagers, said there was still much to learn when she started working with younger children two years ago.

“When I started receiving the training, I thought to myself, ‘Wow, this is what I needed,’” Zamora said in Spanish through an interpreter. When Zamora started rolling out more SEL strategies and lessons in her center, she had children enrolled who had autism and were in foster care. “I needed to navigate this and learn how to deal with my new students,” she said. “Every child … they’ve lived through some really hard stuff. The simple tools that I have learned have had a big impact,” she said.

“We need it, the children need it,” Zamora added.

After several training sessions with All Our Kin, Zamora created a “cozy corner” in her home where children can retreat when they need a calm space. The space has mirrors so the children can see how their faces look when they express different emotions. She also uses a cube that has pictures of the children’s faces and different emotions to encourage the kids to share their feelings and talk about different feelings. Through the training, she has learned various ways to adapt her approach to children based on their emotions, including by whispering to kids who are upset and overstimulated, offering hugs or encouraging children to take time in the cozy corner.

Overall, she said, she feels more confident and secure as an educator. “I have learned to interpret feelings when the child is not able to explain to me with words what they’re feeling,” Zamora said. “I am constantly evaluating myself and re-evaluating the work I do, because these children deserve to grow up in a safe environment,” she said. “Not only physically safe, but safe emotionally.”

While beneficial to educators, officials at Ellis said their work could be bolstered if parents embraced a similar SEL approach at home to further foster student behavior, emotional intelligence and regulation. “It’s so important because if we’re teaching the children about their social-emotional learning here, and then at home it’s not the same, then there’s not necessarily a balance,” said Cherish Casey, a social worker at Ellis. “I think it will really help the children build their social emotional regulation and emotional identity if it’s a full circle, and the family knows the same tools that we’re teaching them.”

This story about social and emotional development in early childhood was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation.